Bay Lines - Beach of Dreams

The Kent & Leven Estuaries - Miles 60 to 80

Mapping 120 Miles of Morecambe Bay through photos, stories and drawings

The Bay Lines - Beach of Dreams project maps 120 miles across Morecambe Bay. In June 2023 artists and walkers from the arts organisation Kinetika walked the whole route of 120 miles around Morecambe Bay carrying silk pennants representing miles of coastline. Their mission - to create 120 new silk pennants, one for each mile of the Bay, to be designed from the mile images and stories contributed by members of the public around the Bay and to be displayed as a coastal art installations at 4 locations across the Bay over August Bank Holiday weekend 2023. The project was commissioned by Ways Around the Bay from the Morecambe Bay Partnership.

Kinetika is working with Kendal-based Rosa Productions as part of a wider multi-year Beach of Dreams exploration of the UK and Ireland coastline.

The is the fourth of five sections - from the estuary of the River Kent to the estuary of the River Levens - from Sandside to Cark. We walk and map the 120 miles of coastline of Morecambe Bay with photos, stories, and drawings from the Bay Lines, Beach of Dreams participants.

Mile 60 - Sandside

Patricia Townsend

Sandside and ‘The Old Man’

Sight of the setting sun and skies ablaze over the shimmering estuary

Attract a regular audience of watchers and waders. As

Night threatens the darkening waters, flocks of sea birds

Dip and dive in anticipation of an evening meal,

Sounds of their success reach a crescendo, while out on the sand the

Incoming tide reminds walkers to be vigilant, as their

Dogs run free, give chase and attempt to catch the wind.

Evening brings rewards as this haven of nature waves farewell to the day.

A

New

Dawn

The water retreats; low tide,

Heat and sun provoke a smile from most; the

Exception is ‘The Old Man’, who beams

On high, in the distance.

Looking down across the bay, he

Doffs his cap, and, in doing so,

Memories in me stir, of another man,

A beloved friend, who often scaled those heights

Now gone - though not forgotten !

Miles 61 - Dallam and Marsh Lane

John Townsend

Mile 61 takes me along Marsh Lane from Dallam Bridge near to the confluence of the rivers Bela and the more dominant river Kent forming the Kent estuary, a major water source into Morecambe Bay. This walk starts to go inland along very flat marshland on one side and rich fertile grazing land on the other loosely following the river Kent upstream. I enjoy this area as it is set with a panorama of hills and Lakeland fells to the west and north, farm land to the east, and the open aspect of the estuary. It is a quiet place with only the sound of the abundant bird life and bleating sheep. A popular place for cyclists and dog walkers, the road mainly used by locals in this small and sparsely populated area.

Although this mile is on the outer most limits of Morecambe Bay, it takes whatever Mother Nature throws at it. The dramatic influence of the spring tides coming in from the bay can leave it flooded, looking like a giant lake, the flood banks unable to cope. It is open to the bitter winter north easterly winds which can be bone chillingly cold, and the fog, so dense that you cannot see a yard in front of you.

However, this section, in the warmer climate gives rise to big beautiful skies and glorious sunsets. Throughout the calendar year I see every aspect of the natural surroundings of this mile. It is diverse and needs to be treated with respect, the local community work hard to manage this land which I appreciate.

My hope is that it can continue into the future and be preserved for future generations.

Mile 62 - Marsh Lane

Patricia Townsend

Mile 62 marks the point at which the River Kent turns tidal and widens into the estuary of Morecambe Bay. The Kent is the fastest flowing river in England, cascading from its source in Kentmere, through Kendal, out into the Bay .

The landscape along this mile has been heavily influenced over many centuries by sea and weather condition which still play their part today. Embankments are present along the coast, protecting agricultural reclaimed land from flood.

Farming is a key industry in this area, evidenced by the hundreds of grazing sheep who flourish on the salt marsh flora and fauna.

Wind blown trees are dotted along the road and stand like sentinels, marking the path of The Cumbria Coastal Way.

The hedgerows are rich in wildlife, with birds dancing alongside you,to keep you company as you walk .

Looking forward, plans are in place to upgrade the sea defences in the years ahead to help this area and its ecosystem adapt to the coastal changes which will be brought about by rising sea levels and climate change.

Mile 63 - Levens

Sue Madden

Source to Sea

Mile 63 is where my own internal map, and the map of Morecambe Bay meet. Living beside the River Kent, watching it rise and fall, has claimed me. I have walked its banks and researched its ecology and history. I have photographed it, filmed it, recorded it, drawn it, printed it, stitched it, and now it has led me to the Bay.

Mile 63. Sue Madden.

When I began my journey, I was looking for the source, but it was elusive. In Hall Cove, where the map says the River Kent rises, I found myself surrounded by water and where the river runs today may not be where it runs tomorrow. Pick a spot and call it ‘source’, I chose the place where I stepped across.

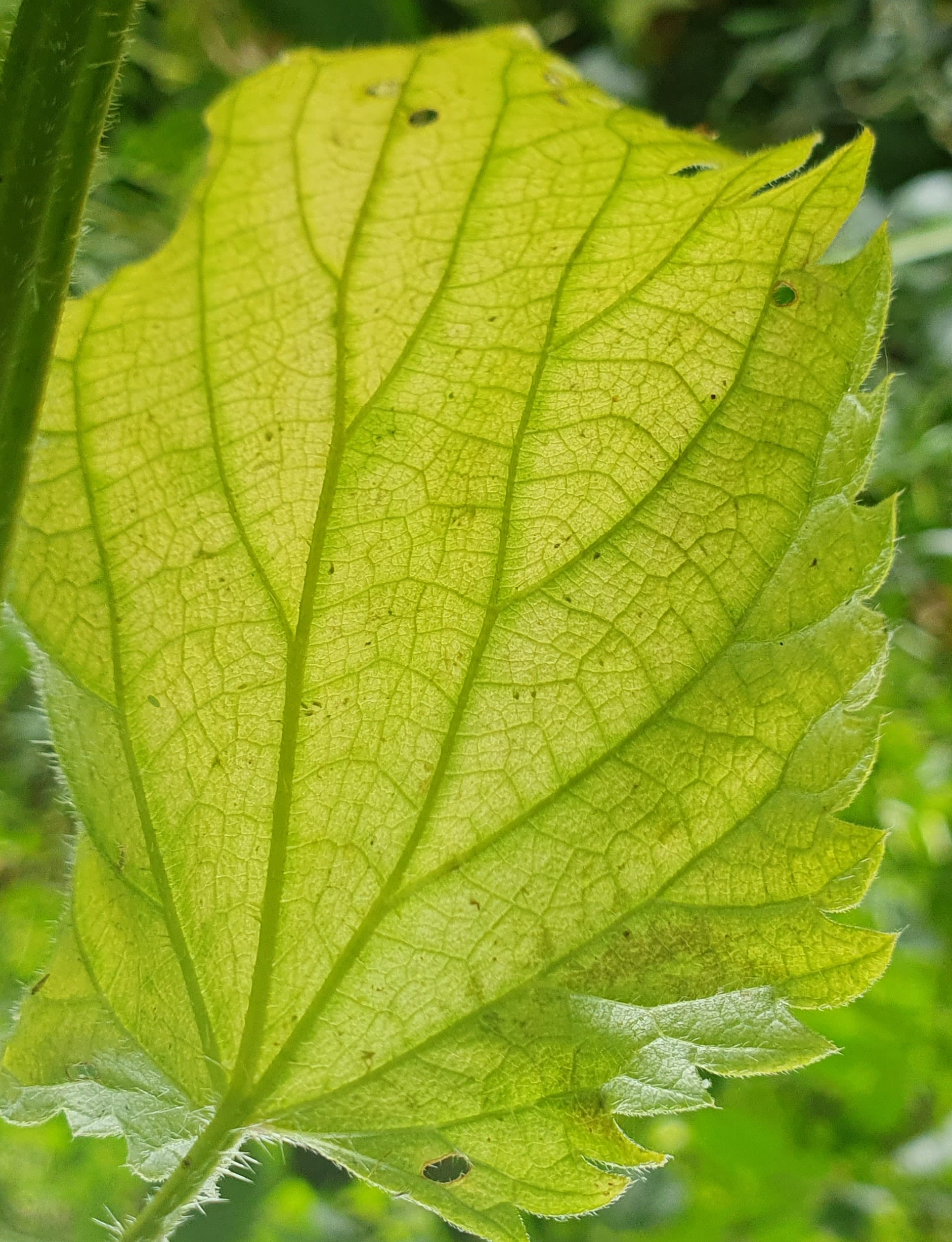

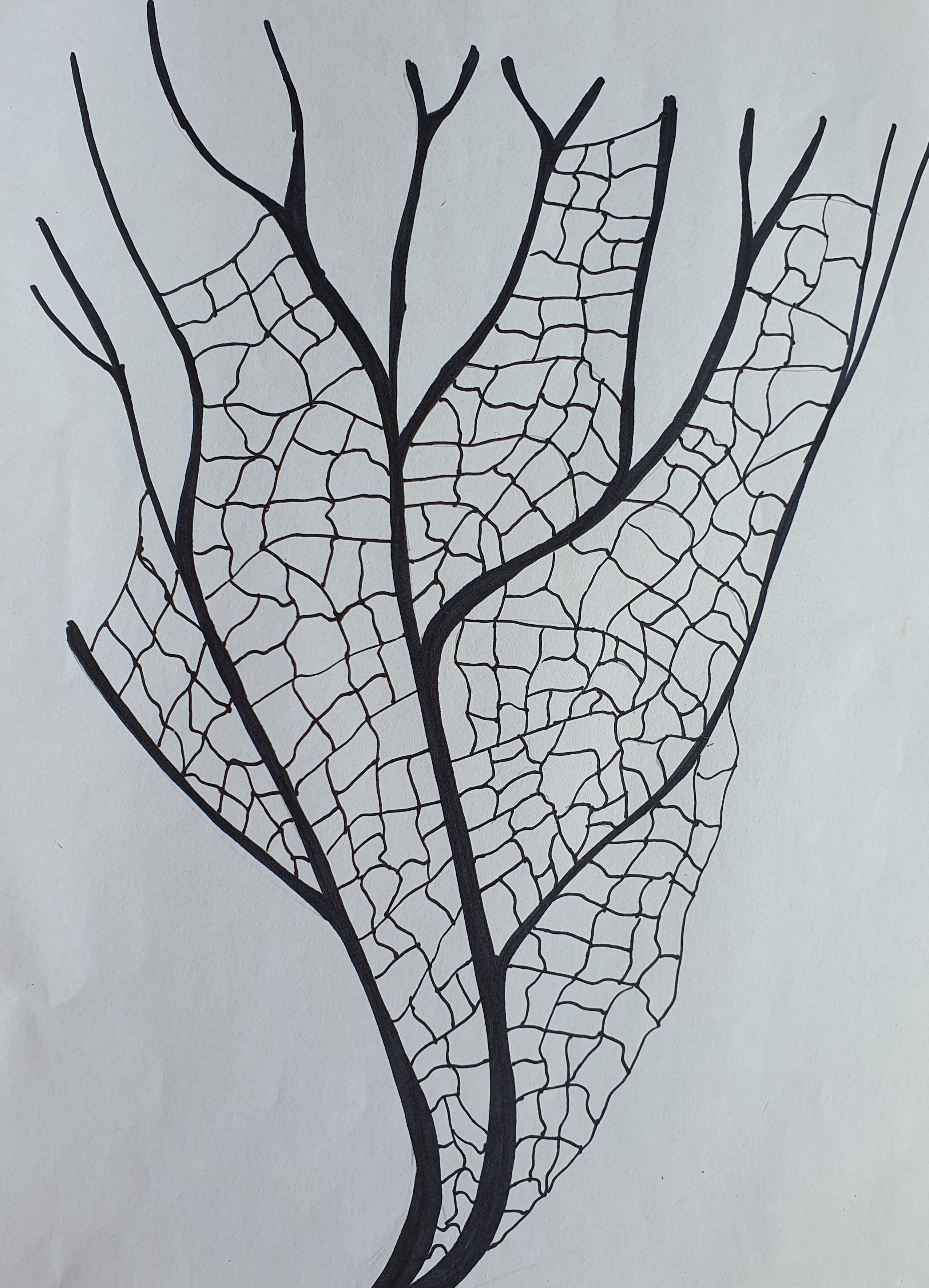

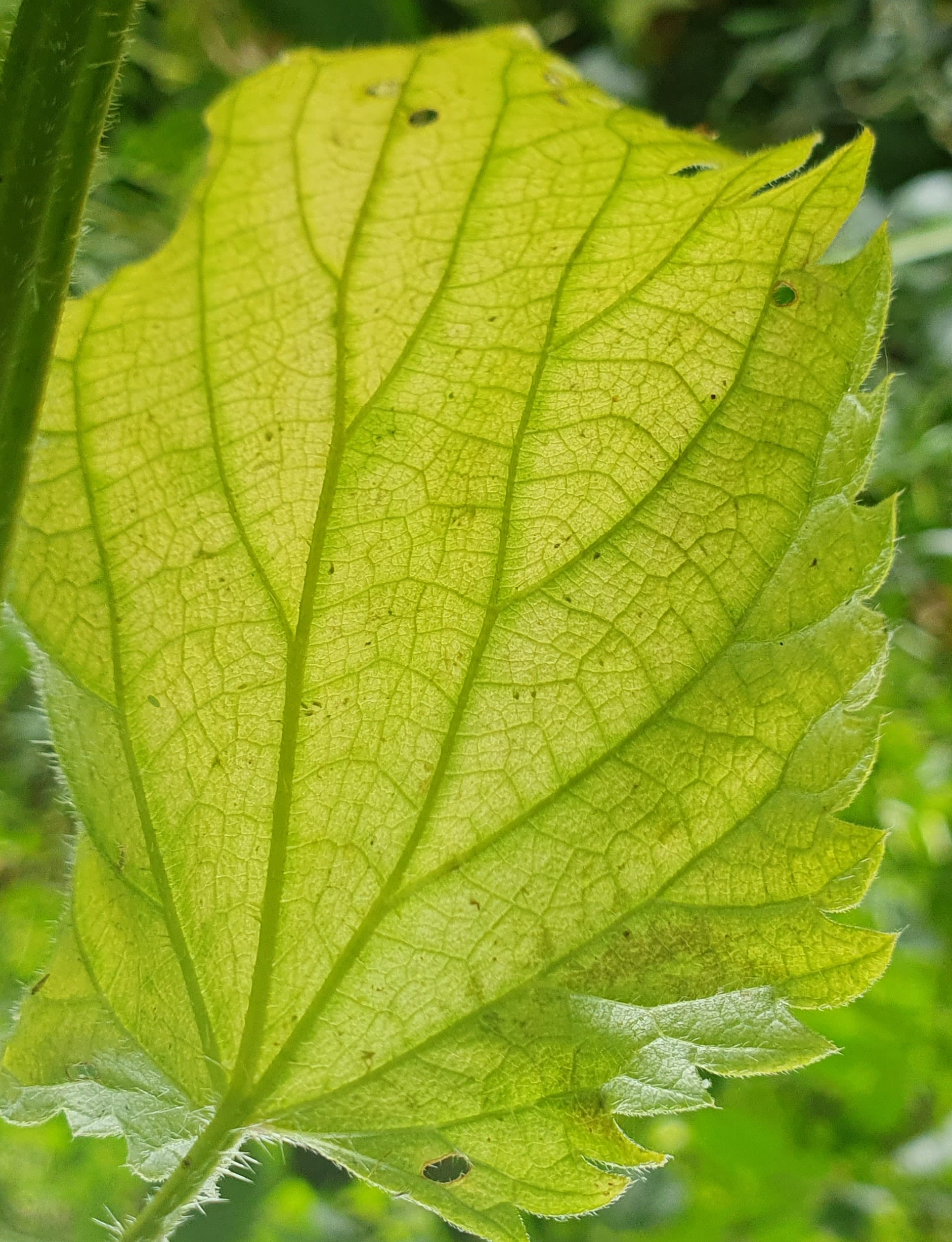

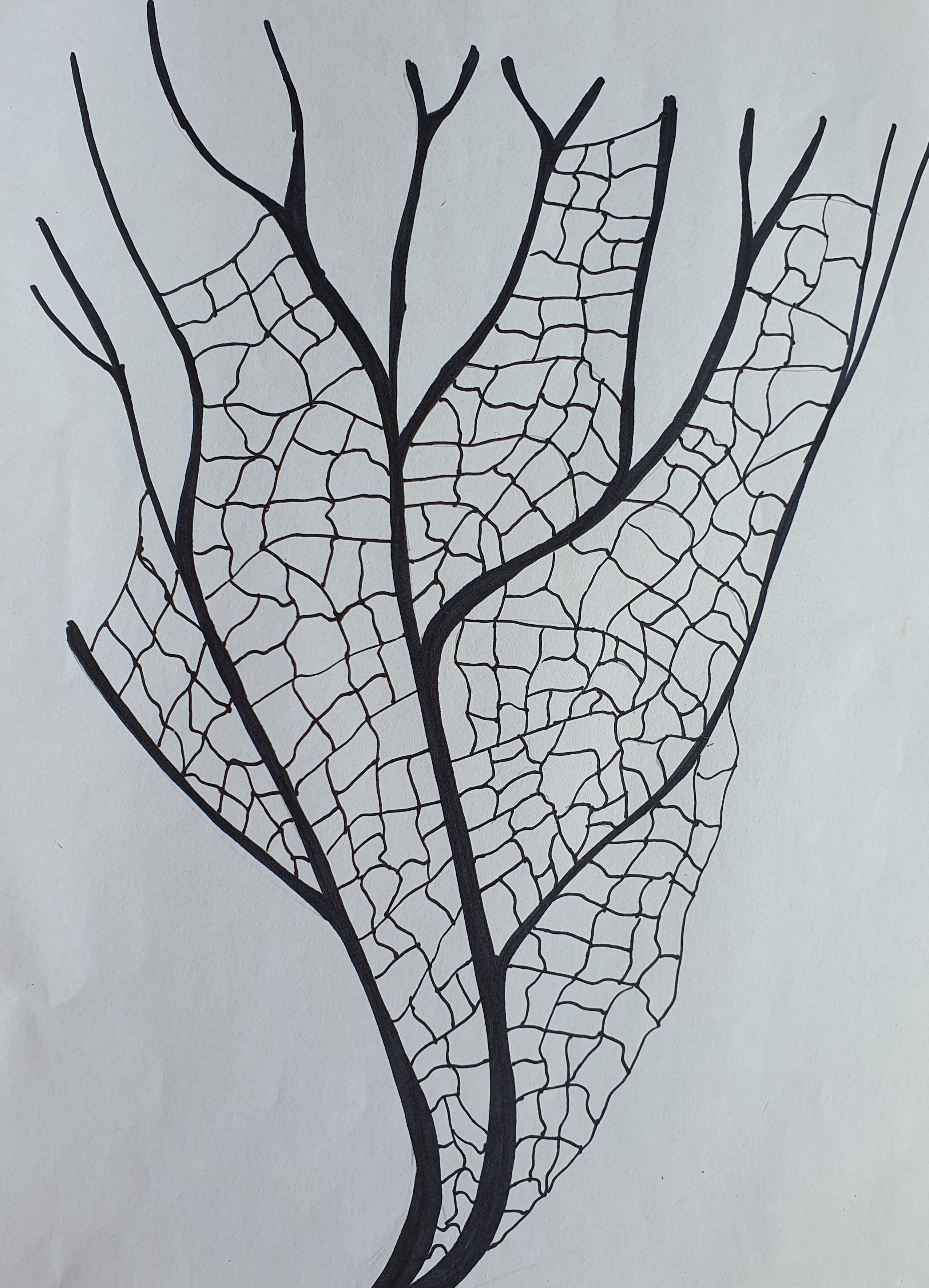

Illustration of leaf veins. Sue Madden.

To find the point where the Kent becomes Morecambe Bay is equally elusive. The Kent and the bay both occupy the same space.

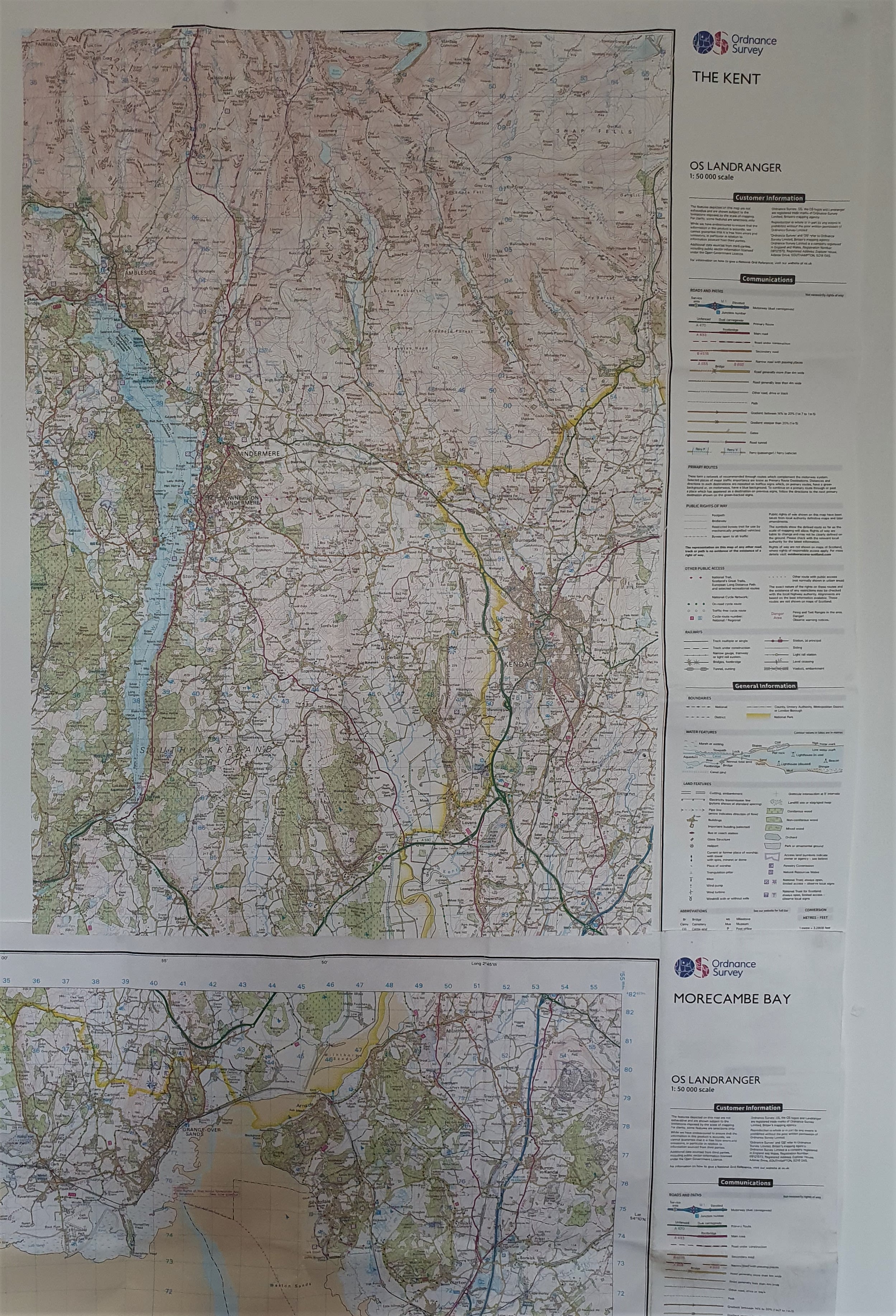

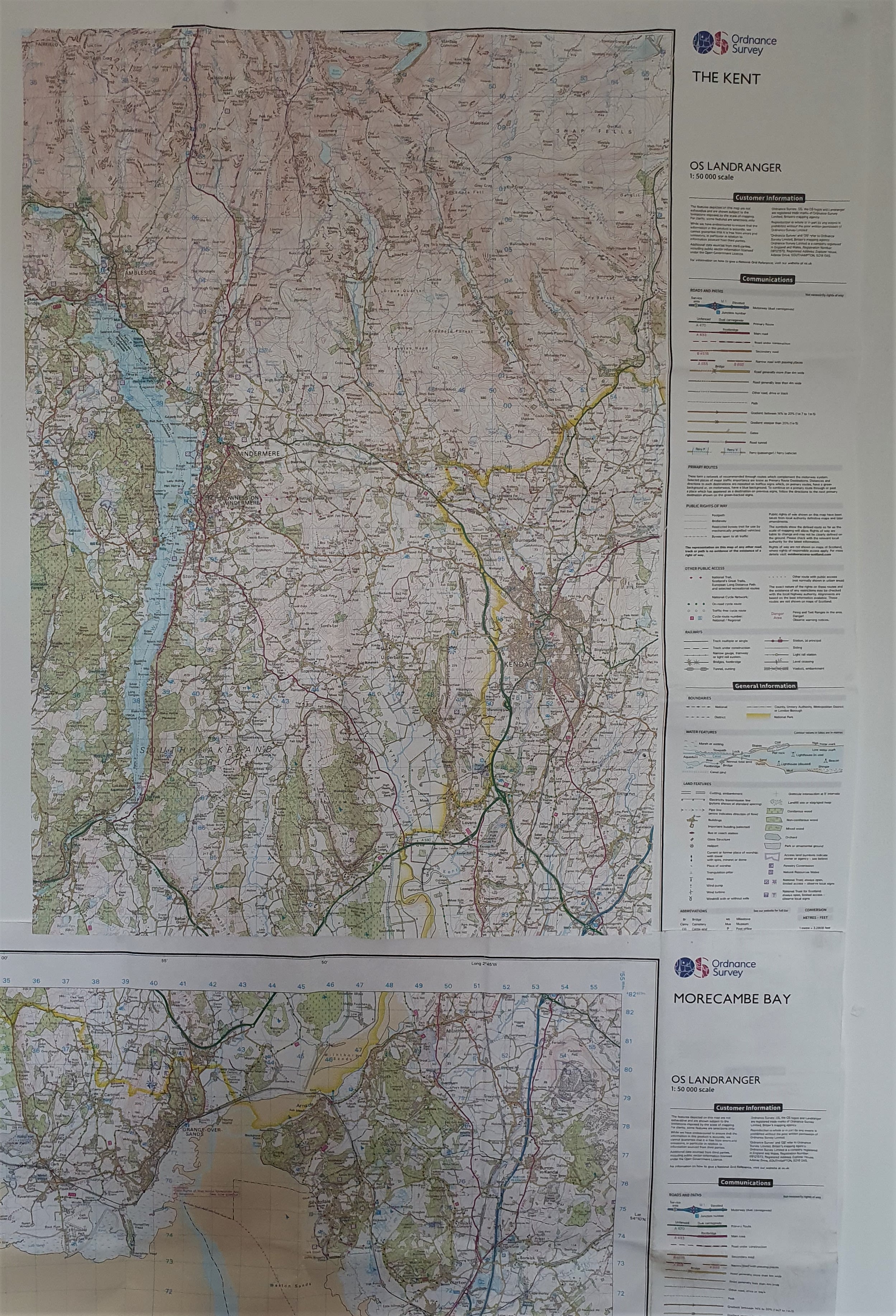

My map - personal and physical. Sue Madden.

‘River’ and ‘bay’ are just words on a map, there is only water, a finite amount of water that has existed on this planet for 4.5 billion years, never a drop more, never a drop less. It endlessly circles around us, but also through us and through every living thing. The water we pollute today will come back to haunt us, it has nowhere else to go.

Mile 63. Sue Madden.

Mile 63. Sue Madden.

Illustration of leaf veins. Sue Madden.

Illustration of leaf veins. Sue Madden.

My map - personal and physical. Sue Madden.

My map - personal and physical. Sue Madden.

Mile 64 Alison Park

My family are dairy farmers near Foulshaw, at Low Sizergh.

There were cows, hens, sheep and beef cattle down on the Moss, along with fairground vehicles, a haulage yard and a few homes.

All around us is this working landscape, formed and re-formed from ancient times to modern times. Farming is hard, the Mosses are exposed, but food is produced there. Salt marsh lamb is flavoursome, tender and to be savoured.

The French have a strong tradition of terroir.

Westmorland and Furness, as we are (again) known, does its best to market its products as dependent upon the rock, the soil, the vegetation. The food from our area is part of our culture.

Walking 'my' mile I was well aware of how restoring it is to be on these edge lands. Nurturing food and and nurturing health. I am grateful to the Bay.

Miles 65 to 67 - Whitbarrow Scar to the Kent Viaduct

Tina Codling, Walks Leader

On Mile 65 the verges are brimming with cow parsley, which is almost obscuring the view of Whitbarrow Scar, a limestone escarpment whose southern end overlooks the Kent Estuary.

The walking group, on the other hand, have only had a few tantalising glimpses of the River Kent as it meanders towards the sea since we left Levens.

There is no right of way along the riverbank here and we are missing the coast and the Bay. As we negotiate a short stretch along the A590 we cross over the Gilpin which rises near Bowness-on-Windermere and joins the Kent before it flows into the estuary.

Tina Codling

On Mile 66 we meet a farmer who asks about the flags we are carrying and, after hearing where we have been, informs me that the Crown does not own all of the foreshore at Silverdale, he does. Shortly after that we pass a fingerpost indicating that we are on the route of the Cumbria Coastal Way, which doesn't officially exist anymore. We are now close to the river but we cannot see it because it is hidden behind a fenced off embankment.

The Cumbria Coastal Way was opened in the early 1990s. It starts at Silverdale, continuing on from the Lancashire Coastal Way, and, after it leaves the Bay, heads up the coast towards the Scottish border.

In 2010, Cumbria County Council told Ordnance Survey it no longer endorsed the route. This was due to it using permissive footpaths which no longer existed. While access rights do exist below the high water mark under the Crown Estate's general permissive consent, the Crown only actually owns around half of the foreshore around England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

And anyway, if there are no rights of way to the foreshore you cannot walk along that stretch of coast.

The new King Charles III England Coast Path is scheduled to be fully open in 2025 but Silverdale is one of the sections affected by these issues. Will they be resolved in time?

Tina Codling

On Mile 67 we are able to climb onto the embankment to see the Kent widen and flow across Milnthorpe Sands towards Arnside.

Over on the east bank we can see Sandside and Storth, where our walk ended yesterday, and ahead we have views of the Kent Viaduct and Arnside Knott.

We are returning to the Bay but we still have several miles to go before we get to Grange-over-Sands.

One day it may be possible to walk or cycle across the Kent Viaduct, adjacent to the railway line, between Arnside and Grange-over-Sands.

A feasibility study and public consultation have been carried out but it is still early days for the project. For now, the only way to continue the walk is to go inland and away from the Bay, as we have done, or walk across the Bay with the King's Guide.

Mile 68 Beth Pipe

We chose this mile because we’re fond of visiting the wreck of the old prawner just below Crag Wood, plus the views from this stretch take in the Arnside Viaduct and Arnside Knott.

The mile itself runs from the road below Ulpha Fell and around to Birkswood Point. It’s rare to bump into anyone else along this part of the route so it’s perfect when you need to escape the crowds.

The prawner is a great example of the boats that used to come in and out of Arnside when it was a busy port, and it’s a tangible example of how the sea, and time, change things.

Over the years that we’ve visited it we’ve seen it decay and break down – it used to have a lot more colour and structure, but now only a few flecks of paint remain and even the iron fittings are rusting away.

Gradually the bay is reclaiming the boat that once relied on it.

Crag Wood is wonderfully unspoilt and a haven for wildlife, even if a visit during the summer months can result in the odd bite or too – even horseflies need to eat, I guess. There’s a path that winds from the gate all the way around the wood, with the size of the views depending on the time of the year and how leafy the trees are

I hope nothing changes in the future, and I hope that by nothing changing, lots of things change. I know that doesn’t make sense. What I mean is that I hope that this corner is left alone and that any changes are down to the natural scheme of things, and not our interference.

Mile 69 and 70 - BOOM

Heather Marples, University of Cumbria

Meathop Moss has been chosen by the Back On Our Map project (BOOM), to showcase the reintroduction of the oblong-leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia).

The moss itself is a Cumbria Wildlife Trust nature reserve and forms part of the Witherslack Mosses Special Area of Conservation.

In the past it has suffered from increased drainage of the surrounding land, which has resulted in many areas of the bog drying out. CWT have been carrying out restoration work, including ditch blocking and cell bunding, to raise the water table again. However, certain species that were lost, have not yet made a reappearance, and that is where BOOM has stepped in.

BOOM is a 4-year Heritage Lottery funded project hosted by the University of Cumbria in partnership with Morecambe Bay Partnership. It aims to reintroduce native species back into south Cumbria with the help of the local community.

The oblong-leaved sundew is one of the plant species included in the project. It is a small, carnivorous plant that has evolved to derive most of its nutrient requirement from captured insects. It requires wet, bare peat next to small bog pools to thrive. It was lost from Meathop when the moss was drier, but after restoration, this habitat is ready for their reintroduction. As this sundew is a poor coloniser, with the nearest donor site over 1 mile away, BOOM had to propagate sundews from the donor population. They were reintroduced into Meathop in August 2022 and within the first month they were successfully catching flies and growing new leaves.

Following a long dormancy over winter, 80% of the population survived and now many of the plants have come into flower! This is exciting news as they will be able to cross pollinate and spread further across the moss in the future.

Mile 69 and 70

Mile 69 and 70

Mile 69. Meathop Moss. Heather Marples

Mile 69. Meathop Moss. Heather Marples

Mile 69. Oblong leaved sundew. Heather Marples.

Mile 69. Oblong leaved sundew. Heather Marples.

Meathop Moss

Meathop Moss

Meathop Moss Nature Reserve

Meathop Moss Nature Reserve

Alex McCartney

Alex is on a work placement with Cumbria Wildlife Trust and explains more about the project BOOM

"Nature is easily one of the most profitable things for human health, whether it's mental health or the fact that we actually rely on nature to bring us oxygen, water and security in terms of food, and so on. So caring about nature from something as small as a sundew to anything as exciting as an osprey is all part and parcel of the same thing.

These are the Great Sundew and Oblong Sundew.

These are part of a volunteer sided project of Boom called Bog in a Box where we would go to mosses where there is healthy and happy populations of both of these species and harvest two leaves from a precise number of plants. So we'd go round a bog count how many there are, and then take only a small fraction of leaves from a small fraction of those plants.

We then collect some bog water with permission from Natural England, and in that bog water you're able to propagate these leaves. So say if we were to harvest this plant, you could take two of these from it, and then those leaves in water would start to grow smaller versions of themselves along it. Follow that forward a few weeks you get volunteers in and you get them to plant in boxes similar to this or like small propagation boxes.

You get them to plant these tiny little leaves on the top of some peat and then those will grow into plants just like this. So these would have all been at the stage that I just described, and those volunteers are able to take those peat boxes home and hence the Bog in a Box, and then they're encouraged to only allow it to be watered with rainwater and that should be enough for them.

Then they'll be returned to Boom. And then we come back and count them year on year to see how the population is doing."

Mile 71 - Meathop Road

Louise Andrews

I chose this mile because I could not picture it despite regularly visiting woodlands nearby.

From the woods there are a couple of places you can look out and across onto the Bay, it looks distant and unreachable.

I wanted to know how to get there and understand what had been keeping me away, I was curious.

When we arrived we had to walk beyond the mile and go over the railway crossing to access the beach.

The sign and the padlock on the gate to our left told us firmly to KEEP OUT...I understood why I had not visited this place before.

Ahead of us was a private island, warning signs to keep away and the gate firmly shut. We turned right and began mile 72....

Mile 72

Nick Andrews - Onto the Grange Promenade

Having owned a small woodland nearby for over 15 years I have never been down to this part of the coast so I was curious as to what I would see there.

The walk was along side a railway line, where I saw some beautiful wild flowers that I did not recognise. I was able to use my smart phone to identify them.

There was a number of different sea birds flying backwards and forwards over the sands and a few dog walkers.

Navigating a narrow pathway up through some natural rocks we came out on the promenade and had a lovely picnic on the bench there. Further along the prom lies Grange railway station and the scenic town beyond.

Mile 73 - Grange-over-Sands Promenade

Aerial View of Grange Lido

Mile 73 - Grange Lido

Bringing our beautiful Art Deco Lido back to life - Fun, joy and pleasure for everyone.

Grange Lido is a stunning example of an Art Deco Lido – It is one of only four surviving seaside Lidos in England and the only one in the North West. It was opened in 1932 to benefit local people in Grange over Sands and Morecambe Bay as well as the growing numbers of visitors and holidaymakers attracted to the seaside and able to come as a result of the opening up of the railways and affordable coach travel.

Photo from Denise Armstrong. Grange Lido in its heyday.

For a brief respite working people could enjoy fresh air, sunshine, being with friends and families and rest and relaxation. What a joy to mix with other young people, to have the freedom of walking around in bathing costumes, to be able to swim and play, a liberation from convention and formality.

Our heritage is not only the buildings that surround us. Our heritage is also about the thoughts, feelings and emotions that we have when we are in those special places. We have the opportunity to combine heritage with health, wellness and community by bringing this unique leisure facility back to life.

Photo of Grange Lido. Katy White.

The recorded memories of local people are key to reviving the Lido. These include those who won trophies in competitions, children who learned to swim in the pool, people who met their future wives and husbands at the Lido and thousands who just had fun!

One of our core priorities is to engage a wider section of the community in the new and invigorated Lido. Working closely with the Eden North project at Morecambe we want to attract differently abled people and those with cognitive and dementia challenges for whom swimming and being in the water can be therapeutic and life changing.

The restoration of the Lido will help to drive regeneration across Morecambe Bay and the peninsula by attracting visitors, creating jobs, providing leisure opportunities and transforming the image of the Bay.

Let’s make it happen.

Photo from Denise Armstrong. Grange Lido in its heyday.

Photo from Denise Armstrong. Grange Lido in its heyday.

Photo of Grange Lido. Katy White.

Photo of Grange Lido. Katy White.

Mile 74 - The Sands Beyond Grange

Mark Ravenhall

A mile from shore the wind is horizontal

making wave ridges in the channel

as the tide turns—

— and turning inland

you see the town rise in tiers

of cream and stone and slate:

bungalows, villas, spa hotels,

the ‘pink palace’, a park, the prom,

tea room, bandstand, tennis courts

a lido where hi-vis jackets swim,

the railway embankment

that ‘created’ this coast

(according to Tourist Information)

brought coal and steel and visitors

to hire ‘bicycle machines’--

all gone under the sand.

But first at your feet:

footprints of those who’ve gone before:

walkers following laurel ‘brobs’

planted along the cross-bay route:

boots, shoes, paws, horses’ hooves—

all printed, all embossed.

This dry month: the creeks dried up,

sandbanks carved by long-forgotten tides,

each designed by water’s action

like sap following a tree’s branch

out to the estuary.

And beyond it, the other side

that always makes a ‘bay’.

Some coasts look out on oceans

but here are hills and trees

and winking lights at nightfall:

caravan parks, luxury lodges, villages,

towns, a city, Heysham B

crouching at the bay’s edge,

a utilitarian shed

less lignum than the sort of shape

the mind airbrushes

while reminding you this is it:

the age in which you live.

The sands are ‘quick’ like us:

alive to changing tides,

temporary, contingent.

Rising waters will come

and rub away our footprints.

By mid-century, they say,

there will be no railway,

no headlights in the deep lanes

over the bay, no laser shows.

Sounds are fleeting too:

the curlews’ call at dusk

the railing of the rails

like stuck pigs.

Martins high above the marsh,

a lone kestrel over the line,

a heron taking off

in loping strides of air.

Sedum in yellow and pink

colonising the limestone

laid by puddlers

in another mid-century.

Nature reclaims everything.

We are the temporary,

the dependent, contingent.

We make our mark,

our mark is rubbed away

like footsteps in the sand.

A coast is land and water both.

Makes us question

What our footprint is.

Mile 75 - Over the railway near Kent's Bank to the estuary.

Mile 76 - Humphrey Head

Michael Green

My German wife and I moved to Grange-over-Sands in 2009 and Anke discovered Humphrey Head, which quickly became her favourite place. Having grown up in post-war Germany with parents who had experienced war trauma she suffered abuse as a child and traumatic events throughout her life.

Humphrey Head. Michael Green.

On Humphrey Head she found solace among the sheep, cows, ravens and peregrine falcons, the rock roses, the ever-changing tides, the sunsets and moonrises. After her untimely death in 2020 we funded a new Cumbria Wildlife Trust information board in her memory at the northern entrance to the site.

Mile 76. Michael Green.

Humphrey Head is a narrow limestone promontory, nearly a mile long, which juts out into Morecambe Bay at the end of the Cartmel Peninsula.

It is owned by Holker Estates, but its grassland has been managed for over 30 years by Cumbria Wildlife Trust.

At the northern end is an outdoor centre for school children and other groups

Seen from Silverdale, Humphrey Head looks like the back of a huge whale rising out of the bay. The east side is covered in woodland, full of bluebells and anenomes in the spring.

The west side is a vertical limestone cliff, nearly 150 feet high and more than half a mile long.

The views from the Ordnance Survey trig point at the top are outstanding - the Furness Peninsula to the west, Lake District hills to the north, and to the east Ingleborough and the Yorkshire Dales, the Forest of Bowland and the Lancashire coast as far as Blackpool Tower.

Cows and sheep graze the grassland, peregrine falcons and ravens nest in the cliffs and rare flowers can be found among the rocks.

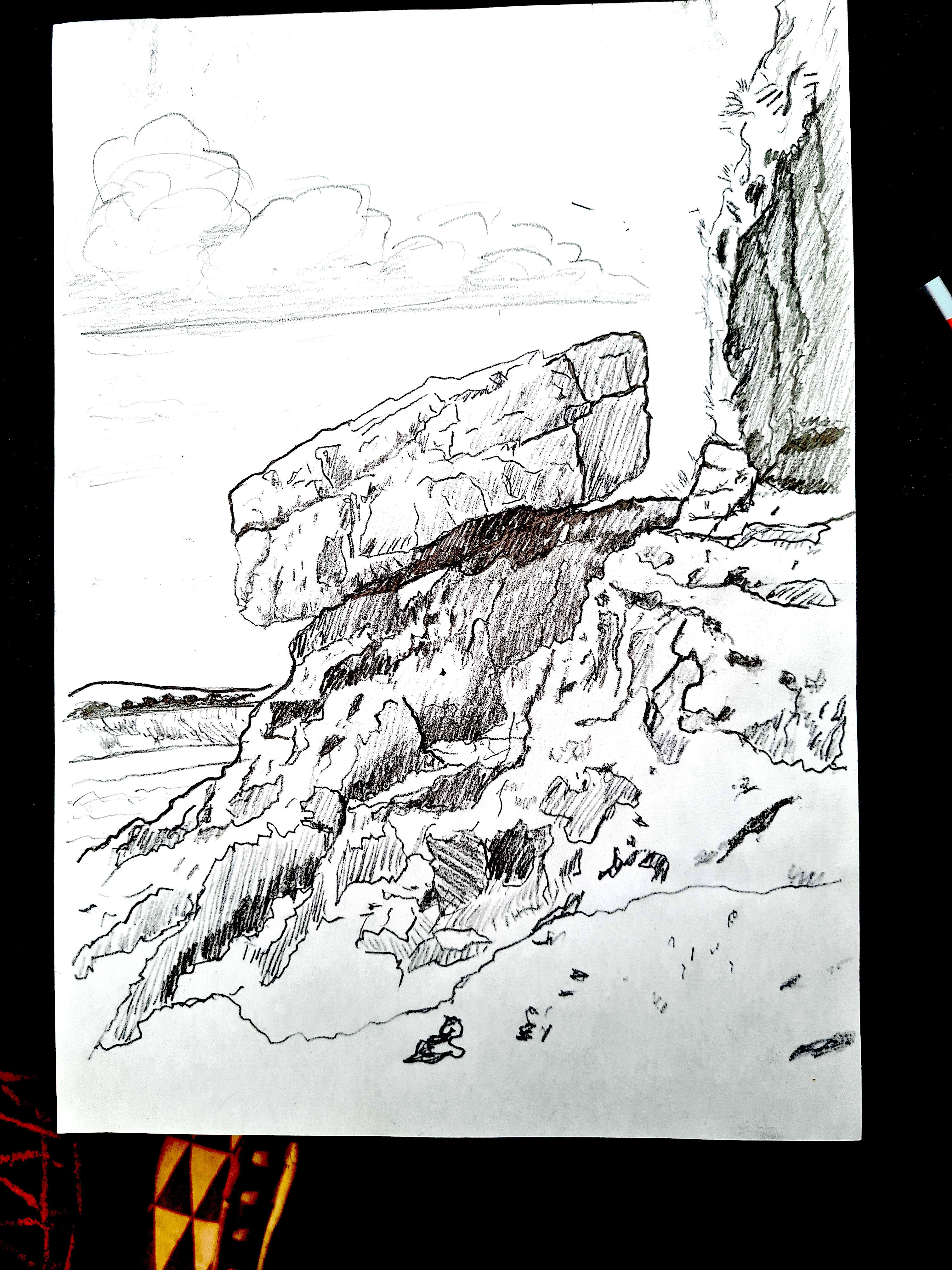

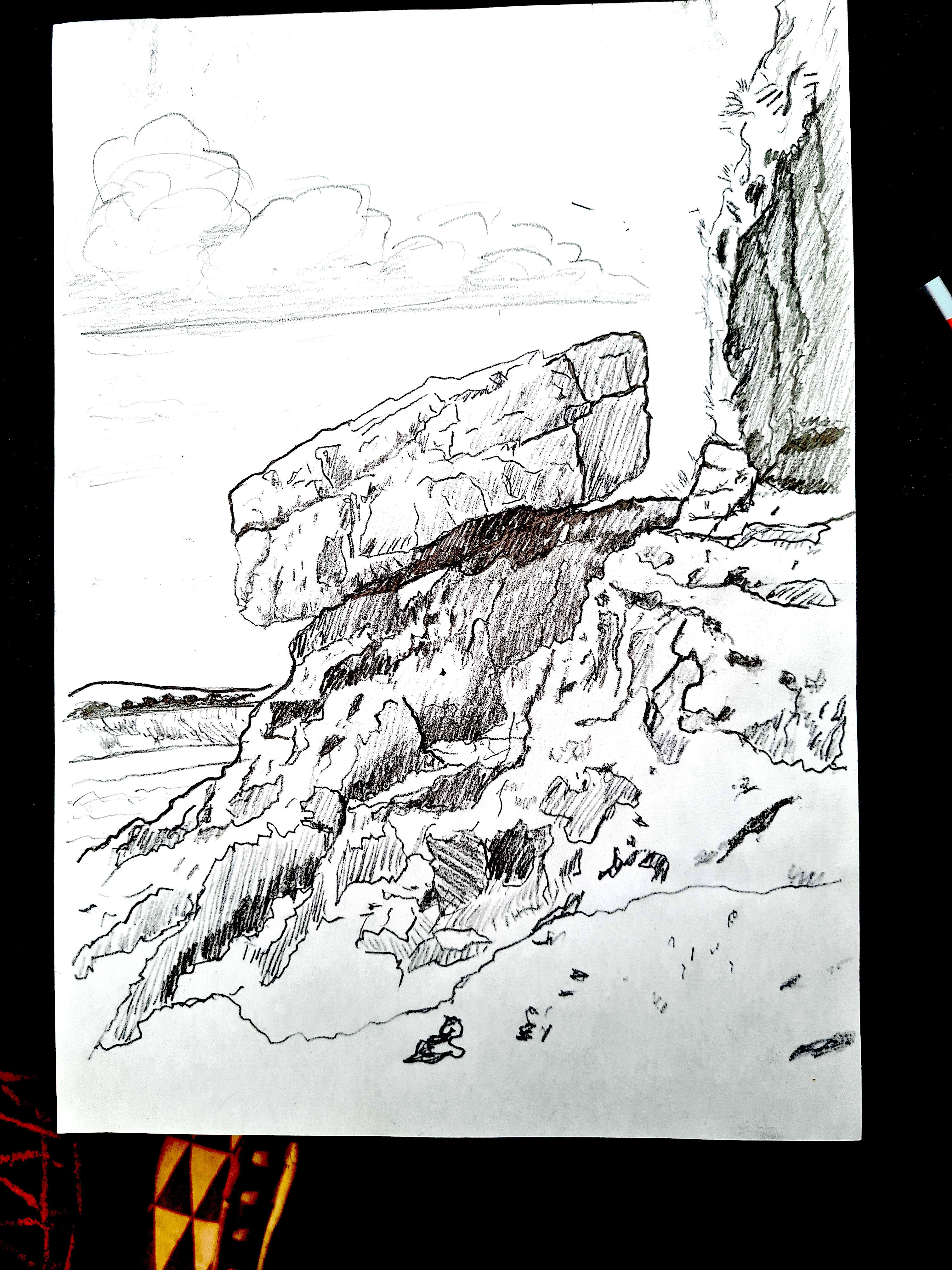

Balancing boulder. Michael Green

There is a huge arch near the top of the cliff, and jumbles of rocks along the bottom. Channels loop around the rocky southern tip, which points towards Heysham power station, and here are often quicksands close to the shore. At high tides the sea reaches to the bottom of the cliffs.

“The Holy Well”, signposted at the turn off from the road to Allithwaite is just a trickle of brackish water at the bottom of the cliff.

It has been claimed to have healing properties but this cannot be recommended by me.

Illustration of boulder for pennant. Michael Green

The south end of Humphrey Head can be reached by paths through the wood or over the top. At low tide in the summer it is possible to walk to the end along the bottom of the cliff.

Humphrey Head. Michael Green.

Humphrey Head. Michael Green.

Mile 76. Michael Green.

Mile 76. Michael Green.

Balancing boulder. Michael Green

Balancing boulder. Michael Green

Illustration of boulder for pennant. Michael Green

Illustration of boulder for pennant. Michael Green

Mile 77 Gemma Wren

Tales of wolves, windswept trees, ever changing views and the diversity of life clinging on to the edge all draw me to Humphrey Head.

This wild exposed, untamed headland pokes out from the bay coastline creating a prominent finger of biodiversity.

There are so many layers to Humphrey Head that showcase the wider beauty of the bay area – saltmarsh and sand shaped by the sea, limestone outcrops and trees shaped by the wind, limestone grassland full of wildflowers and butterflies nurtured by the sun. A blending of colours from brown, grey and green to orange highlighting the texture of the landscape.

Standing beneath the limestone ‘head’ it looks like you’re on the edge of an endless swamp: the distinctive smell of salt marsh, the bleating of the marsh sheep as they munch through the nutritious plants that grow there and the shrieking of the swifts and swallows as they bomb around in the air, feeding on the rich insect life that hums above the land. Discarded crabs from hungry sea birds litter the shoreline, in between sparse stands of succulent saline plants.

I love the way the view changes as the light and tides move, and the change in perspective from below and above.

The view above from the limestone headland shows the shapes and patterns of the saltmarsh forming braided channels, creating a soft edge to the landscape between sea and land. Wildflowers flow over the sides, clinging on in nooks and crannies that capture the rich sea air. The grasslands change from yellows, purples and pinks in the summer to an array of oranges and reds of the waxcap fungi in the autumn.

For me - a place of discovery, quiet contemplation and blowing away the cobwebs.

A hope that this ever changing place never changes.

Mile 78 - Saltmarsh between Humphrey Head and Flookburgh

Sarah Mason, Morecambe Bay Partnership

This mile is close to my home and I walk it regularly.

The saltmarsh in the area is vitally important to breeding shore birds and I would love to see the site protected for these creatures into the future.

Every year, disturbance from humans increases in this area, through illegal access as people do not understand the impact they can have on these fragile ecosystems.

Farming practices are not in tune with nature and there are too many sheep grazing the marshes, leading to trampling of bird nests, eggs and chicks.

The sounds of the marsh here are the most evocative in the countryside; curlew, skylark, lapwing & redshank all try to breed often with limited success.

Eider ducks can be heard calling from the deeper water of the Bay. This area is beautiful & could be so abundant with nature if we gave it space to thrive.

Mile 79 - Flookburgh

Lyn Prescott

Willow Lane through the ages

I’ve lived in Flookburgh for over 20 years and Willow Lane is half a mile from my home on the route from Flookburgh to Humphrey Head. I’m interested in the history of the area as well as developments in more recent years which can be seen as you go along the lane.

In the 15th Century Wraysholme Tower was built, reputedly by the Harrington family, just north of the east end of the lane. The last wolf in England was said to have been killed on nearby Humphrey Head by a Harrington of Wraysholme Tower.

Mile 79. Lyn Prescott.

Half way along the lane is Holme Farm, which has been occupied since at least the 17th Century (James Milner of the Ho[l]me was buried on 11 March 1605 in Cartmel churchyard). At the turn of the the 18th and 19th Century land on both sides of Willow Lane was enclosed as part of the 1796 Cartmel Enclosure, which was one of the largest enclosures in England, and included the building of an embankment to the south of the lane, which prevented the previously regular flooding. Also in the 19th Century the Lancaster & Ulverstone Railway company build a railway line north of the lane, opening in 1857, with a crossing near Wraysholme.

Willow Lane. Lyn Prescott.

The 20th Century saw an RAF Base, houses, a caravan park and a scrapyard develop on the western part of the Lane. In the 21st Century an alpaca farm has been established, Wraysholme Dairy is now supplying a range of dairy products direct from the farm and the new Bay Cycle Route was opened which includes Willow Lane.

Mile 79 Line Drawing for pennant. Lyn Prescott.

The uses of the lane will continue to change and develop but if you look closely you will continue to see its history along the way.

Mile 79. Lyn Prescott.

Mile 79. Lyn Prescott.

Willow Lane. Lyn Prescott.

Willow Lane. Lyn Prescott.

Mile 79 Line Drawing for pennant. Lyn Prescott.

Mile 79 Line Drawing for pennant. Lyn Prescott.

Mile 80 - The Leven Estuary

Linzi Buckmaster

I selected Sandgate, Mile 80 at Cark, as my mile because I spend so many hours there, watching , waiting and taking many photographs, it seemed an obvious choice. Very local to where I live I try to go there as often as possible to decompress and recharge.

The wide open spaces and huge vista of marsh, sand and sky looking around from the Coniston Fells to Piel Island it is always peaceful regardless of the weather.

Looking across the Leven Estuary to Ulverston there is a great view of Hoad and the hills beyond with ever-changing light. The sunsets here are fabulous and some evenings you have the whole place to yourself. With the sound of the wind turbine and birdsong it is vitamin sea for the soul.

Carpeted in flowers depending on the season with the salt marsh pools sometimes full , other times dry and crazy-paving cracked and the sand rippled, marble dry or treacherously slippery there is always nature to appreciate.

The old trailers loaded still with shrimping gear add to the ambience and they make great perches for the Skylarks.

My hope for the future is that channels could be free from sewage, pollution and rubbish. For the bird life to flourish and for people to continue to enjoy the views , take only photos and leave only footprints.

Mearness Point

Gina Parker Mullarkey and Zac Parker

This is a walk we regularly do as a family straight from our door.

We love the changing landscape of Mearness Point, which can become inaccessible during the spring high tides.

My son, Zac, loves running around with our dog (on a lead) exploring and finding treasures, digging in the sand, jumping channels and climbing on the rocks (which once seemed like huge cliffs to him when he was smaller).

We love a wander in particular to 'our secret beach' where there is rarely another soul to enjoy a picnic with a view across the estuary to the hoad.

Picnics in the sun are special, but splashing in wellies or even in the snow means that Mearness point gives us pleasure all year. Of course we don't venture out onto the' sinky sand'.

My eldest now enjoys strolls down here on their own with friends, so it is a place for us all to enjoy.

The fifth and final part of the journey around Morecambe Bay can be found in the Ulverston to Walney Island section.